Menashe Kadishman by Arturo Schwartz

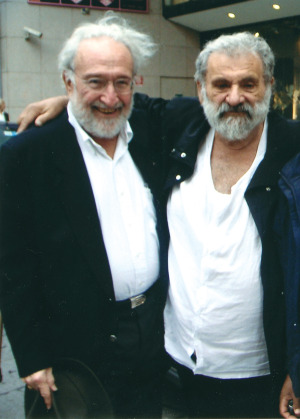

On a bright May morning of 1993 Ofer Lellouche told me, “you must meet Menashe Kadishman, you will like him, he is a Flabelaisian personage, and one of our most important sculptors.” At the time my knowledge of lsraeli art was very poor, I remembered his performance at the Venice Biennial of course, but was not familiar with his further developments. I asked: “what kind of sculpture does he make now?” Lellouche’s Iapidary answer perfectly epitomized the personage, with a smile: “He sculpts as a painter and he paints as a sculptor.” The appointment was made for the following day in his Tel Aviv studio. Lellouche, my wife Rita and I arrived a few moments before the set time and we waited for him at the top of the staircase. A big – really big – man appeared, dressed as always in his uniform: a white shirt floating over white shorts, and holding three brightly colored balloons, in the shape of a mermaid and two Disney characters, flying high above him. He climbed the stairs with an agility that contradicted his weight.

On a bright May morning of 1993 Ofer Lellouche told me, “you must meet Menashe Kadishman, you will like him, he is a Flabelaisian personage, and one of our most important sculptors.” At the time my knowledge of lsraeli art was very poor, I remembered his performance at the Venice Biennial of course, but was not familiar with his further developments. I asked: “what kind of sculpture does he make now?” Lellouche’s Iapidary answer perfectly epitomized the personage, with a smile: “He sculpts as a painter and he paints as a sculptor.” The appointment was made for the following day in his Tel Aviv studio. Lellouche, my wife Rita and I arrived a few moments before the set time and we waited for him at the top of the staircase. A big – really big – man appeared, dressed as always in his uniform: a white shirt floating over white shorts, and holding three brightly colored balloons, in the shape of a mermaid and two Disney characters, flying high above him. He climbed the stairs with an agility that contradicted his weight.

I soon found out that his overabundant physique mirrored a boundless enthusiasm, an exuberant vitality, and an extraordinary generous character- a 360″ generosity: in his feelings for relatives, friends and fellow artists, in his artistic output, in his creative means. His is an inborn munificence and benevolence that I have rarely met in other people. We came into his three-room studio-deposit, crammed with paintings and almost stumbling over two sculptures. Thus started a friendship which, as far as I am concerned, is motivated as much by the admiration I have for the artist as by the appreciation I have for the man whose sense of humor and warmth is unequaled. The artist’s “appropriation” of the outside reality may have many different motivations, with the New Realists – like Arman and Spoerri – or the “decollagistes” – Hains or Rotella for instance, it may be a formal technique, sublimated in the poetics of the action, with the intent to achieve an aesthetic result. With myriam Bat Yosef, as has just been seen, it is the expression of the wish to recreate the world in the image of her dreams, hopes and desires. With Kadishman, appropriation is the manifestation of a boundless love for nature and its off-springs whether animal- as is the case for the sheep – or vegetal – the trees. But Kadishman’s appropriative outlook also reflects the holistic character of his ceuvre: he wishes to merge man and nature, the organic and the industrial, sculpture and painting. When Kadishman says: “I believe that art grows from feelings and not rational calculations alone” I think that he was too shy to substitute “feelings” with the word “love” since I suspect that what he really meant was that art grows from love.

Trees and sheep have a clear autobiographic origin and also a very special meaning in Kadishman’s personal mythology. Concerning trees, his feeling for them started when, still a child, he was taught to plant trees to defeat the desert. To celebrate the 25th anniversary of the Israel Museum he painted a nearby tree, commenting later: “The tree is near to my heart ….

The ‘Painted’ Tree has been an act of love, a sort of personal declaration. A phase within a prolonged attempt to intermingle with nature.”

And explaining the reason for this act of love as well as the place it occupies in his imagination: “There ls both an affinity and a certain equality between us: the tree is the Man of the silent world; our language is filled with trees: the tree of the field is man’s life, the bramble allegory,the trees die standing, the cedars of Lebanon.” Kadishman started making environmental work in the mid-sixties: he dug holes in the earth and filled them with Broken Glass “in order that they grow glass trees in your imagination.”

He was thus reenacting the fertility rite of his childhood with broken glass in the shape of frozen water. He began working with actual trees in 1969, in the course of an international Sculpture Symposium in Uruguay’s capital Montevideo. He had arrived with a finished sculpture with the intention to set it up there. However the atmosphere of silence and tranquility, the fact of being in a completely different world made him realize how extraneous to this new reality was the artifact he had brought, it “might have been ‘untrue.’ It gave some kind of a jar, impossible to ignore. It was a forest that lived by itself, and the sculpture was a european sculpture living a ‘European life.’ I wanted to work with the forest God had created, the organic forest, and to fit into it a mechanical forest, a man-made forest containing forms that would be a contrast to nature.” Here the fusion of the organic and inorganic was achieved by nailing yellow-colored hard-edge steel plates onto eucalyptus trees scattered within the 2-3 acre Roosevelt park in the outskirts of Montevideo, creating thus a “Forest Within a Forest”.

Kadishman explained: “The yellow plates reflected the shadows of the branches and stems that were changing together with the moving sun. Nature has thousands of forms which are changing as the sun moves. A yellow such as mine is not to be found in the color scale of the forest. The organic trees, the industrial plates, the changing shadows over the plates, all became one unit. It was beautiful. Almost like ritualistic magic.” The following year, 1970, within the frame-work of an exhibition at New York’s Jewish Museum, he set up in Central Park, along Fifth Avenue, his own Forest.

A completely different environment necessitated a fresh treatment: “The rhythms I have created were more related to my Glass-Metal sculptures. A block and a  space, with a stain of color on the tree and a space extending up to the next tree. The passing yellow cabs of New York, the fixed plates. the shadows of trees and cabs, the lights of the changing traffic-lights – all these created a technological urbanistic forest. My yellow was very familiar here. The yellow plates moved from the stillness of the Montevideo forest to the turmoil of New York’s Fifth Avenue.” Still another approach was realized in 1971 at Krefeld, in the course of his solo-show at the Haus Lange Museum. On the trees of-the park surrounding the building he hung tall rectangular iron sheets painted yellow – offering a strong color contrast with the surrounding green and brown dominant tones – and square panes of glass which acted both as a reflecting surface and a deforming one: the time was mid-winter and, in accordance with the degree of moisture frozen on the glass, the reflection of the trees changed color and form and the stems appeared distorted. Kadishman recalls with pleasure that it looked like “a frozen glass forest. Like a legend. Now my forest had colorful trees, transparent plates, and shadows.” From dry land to the water was Kadishmans next move. In 1975 he cut tree-shaped apertures in steel-plates which were then dipped into the sea of Caesarea: as the water passed through them, the waves generated the trees. From harnessing water to create elusive and dynamic trees to using air for the same purpose was the next logical step. It was taken that same year within the context of the Israel Museum’s group show From Landscape to Abstraction.

space, with a stain of color on the tree and a space extending up to the next tree. The passing yellow cabs of New York, the fixed plates. the shadows of trees and cabs, the lights of the changing traffic-lights – all these created a technological urbanistic forest. My yellow was very familiar here. The yellow plates moved from the stillness of the Montevideo forest to the turmoil of New York’s Fifth Avenue.” Still another approach was realized in 1971 at Krefeld, in the course of his solo-show at the Haus Lange Museum. On the trees of-the park surrounding the building he hung tall rectangular iron sheets painted yellow – offering a strong color contrast with the surrounding green and brown dominant tones – and square panes of glass which acted both as a reflecting surface and a deforming one: the time was mid-winter and, in accordance with the degree of moisture frozen on the glass, the reflection of the trees changed color and form and the stems appeared distorted. Kadishman recalls with pleasure that it looked like “a frozen glass forest. Like a legend. Now my forest had colorful trees, transparent plates, and shadows.” From dry land to the water was Kadishmans next move. In 1975 he cut tree-shaped apertures in steel-plates which were then dipped into the sea of Caesarea: as the water passed through them, the waves generated the trees. From harnessing water to create elusive and dynamic trees to using air for the same purpose was the next logical step. It was taken that same year within the context of the Israel Museum’s group show From Landscape to Abstraction.

From Abstraction to Nature, for which Kadishman created his Canvas Forest he cut the minimalist outline of trees into six meter-high sheets of gray canvas. As they were blown by the wind like sails on the sea, they gave visitors the impression of moving through an animated, enchanted forest. Today a small cluster of blue tree-shaped flat metallic sculptures can be seen in Jerusalem’s rehov. Ultimately all the environmental work – which from the mid-sixties occupied his mind – reflects his desire to transcend the nature-culture polarity in a work of art and hence merge “the thousand forms of nature” with the limitless forms born of his imagination. Paul Wember pointed out: “Nature is also form. The plant-world produces new shapes constantly – according to a plan.They are not free. Constraint and freedom face each other here. Perhaps the tension between them is the core of Kadishman’s intention. Constraint: the principle of nature; freedom: the principle of art. He tries to build a bridge between the two.”

For Kadishman, the step from static vegetal “Readymades” to animal ones was as short as the one that took him from land art to body art, the bodies being those of the live sheep whose fleece he tinted blue and exhibited at the Venice Biennial in 1978 in honor of that year’s theme “From Nature to Art – From Art to Nature.” By color-marking the sheep, the ex-Kibbutz shepherd gave an artistic dimension to the customary practice of staining the wool of the animal’s back with the color of the herd to mark its ownership. At the same time he composed an ever- changing “tachiste” painting, as Amnon Barzel remarked: “The blue painted stains are moving, drifting apart or coming together according to the sheep’s movements and needs. The biology, the animals’ behavior determine the form of the ‘picture’ which is composed of the total number of blue stains.” To Barzel, Kadishman also said: “I want my work to exercise all the senses. Even those abandoned by art. Smell, sounds, touch. Now, in Venice, in the pavilion populated with sheep that move, chew and dung – the spectator exercises all of his senses, because I demonstrate a segment of real life. I do not want an ant with a capital A, with order and discipline, with ‘correct and incorrect.”‘ For Kadishman “sheep are not simply a part of nature, but unfold on a deeper existential level. They are a mirror and a memory.” To Barzel, commenting also on the tree and the grave, he said, “The sheep, the cypress and the grave are actual memories of a beloved site, a place of intimacy in the land of Israel. All these have become a symbol because the reality which gave birth to the memories have disappeared.

The romantic reality becomes nostalgia, and a symbol. We need both nostalgia and symbols in times of loneliness, when the roots have gone from us and vanished.” In the last analysis, sheep symbolize for Kadishman the unending quest for identity and belonging as well as the end of the wandering of the Jewish people. The BienniaI’s live sheep gave birth to a countless progeny: in both painting and sculpture – of endless variations on the theme, the outline of the sheep’s head even becoming his favorite logo.