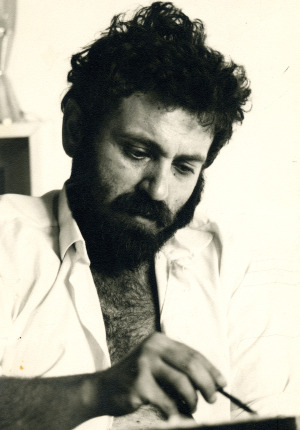

‘Menashe Kadishman’ by Edward E Fry

In the collective mind of the art world of New York, and thus of the United States, Menashe Kadishman securely occupies a distinguished position defined by his sculpture of the late 60’s and early l970’s, in which he absorbed the precepts of Anthony Caro and his circle and then transformed them into a phenomenological drama of levitation, of unexpected combinations of metal and glass, and of minimal forms which soon broke away into nature from the asceticism of the urban cultural world. But during this entire earlier phase of his work Kadishman also led another life within himself nourished by his youth in Israel and by his sense of the moral dimensions of existence, of the sacredness of humanity within a secular world ringed with death. The tension between these two worlds, one the narrow formalit-phenomenological orthodoxy of a dying modernism, the other of a compassionate moral imagination engendered by man’s historical condition, could only lead to a convulsive transfiguration of his art.

In the collective mind of the art world of New York, and thus of the United States, Menashe Kadishman securely occupies a distinguished position defined by his sculpture of the late 60’s and early l970’s, in which he absorbed the precepts of Anthony Caro and his circle and then transformed them into a phenomenological drama of levitation, of unexpected combinations of metal and glass, and of minimal forms which soon broke away into nature from the asceticism of the urban cultural world. But during this entire earlier phase of his work Kadishman also led another life within himself nourished by his youth in Israel and by his sense of the moral dimensions of existence, of the sacredness of humanity within a secular world ringed with death. The tension between these two worlds, one the narrow formalit-phenomenological orthodoxy of a dying modernism, the other of a compassionate moral imagination engendered by man’s historical condition, could only lead to a convulsive transfiguration of his art.

This rebirth would carry Kadishman first away from art into life and then, through countless drawings, back into art again, first to painting and then, finally to a pictorially inflected sculpture. But this new sculpture by Kadishman is no longer the sculpture of modernism, despite the artists absorption of the entire modern plastic tradition; for the sculptural tradition of modernism was the record of private, individual, aesthetic and subjective experience which, when transplanted into public space, carried its homelessness and social alienation with it and was at peace with its surroundings only within the bourgeois subjectivity of the modern art museum or the secluded garden.

Kadishman’s new sculpture is instead a truly public, social and therefore monumental art which, though it depends on a previous tradition of modernism, has its subject a group of themes and issues that transcend the mythology of Kantian self-definition and progress toward aesthetic purity This new sculpture is, from the old modern standpoint, impure, but it is nevertheless, neither anecdotal nor illustrational. lts focus has simply shifted from the aesthetic mythologies of the old modernism to another set of myths and to the very real social and human consequences of those myths; myths therefore operate within the consciousness of the individual not only in isolation but also as amember of human society.

Few men, and fewer artists have the courage to discard the safe path that led to their early success, public acceptance and even their personal identity. In art as in life, early triumphs too often condemn the victor to endless repetition and a devolution into inertia of self-parody or at best, into an existence as the reified purveyor of objects and professional services. But Kadishman is not the first artist to have taken such a step, from the myth of art to life~in~art through myth. His predecessors are the Picasso of Ma Jolie but also of Guernica and notably, among sculptors, the Jacques Lipchitz of crystalline cubist guitarists but also of

Prometheus and the tree of Life. It is a most difficult, because almost always misunderstood, transmutation from form and style to meaning and value; and it is almost always an inescapable response to the convergence of personal and historical crises. For Picasso and Lipchitz, it was the rise of facism and its threat to all of European civilization in the l930`s; for Kadishman, the crisis of lsrael in the l980’s.

Israel is the dream come true for millions of victims and outcasts; it is an island surrounded by enemies yet victorious through three wars in forty years; it is the child of America, Europe and the Enlightenment yet older than its parents; and it is also the stage on which is enacted, in the name of national survival, the conflict between the facts of power and the reality of traditional moral ideals. This is a conflict which knows no boundaries, descending upon all communities and cultures as they expand and harden through social entropy into entrenched civilizations, with wars to win and wealth and territory to protect even at the cost of their very identities and their collective souls. lt is the tragedy of the world as we know it, performed with a special vividness in Israel on a small and local scale yet with universal significance.

Kadishmans insight was that this great theme could be the basis of a monumental art; and his genius was to find a mythic structure to embody and convey that theme. His choice was the Sacrifice of Isaac {Genesis 22:1-l9), a foundation of Judaism, in which Abraham was tested by (Sod to obey His command to sacrifice his son; when Abraham obeyed, his son was spared, a ram was sacrificed instead, and Abrahams absolute trust in God was vindicated. But Kadishman then transformed this mythic structure by rendering it in secular terms even while retaining its original meaning as an ironic residue. The absolute obedience to God thus became the obedience of citizens to the political and military power of the state. But nation~states send their young men to war, and the young men are not spared but die, their corpses eaten by dogs and vultures; for in the secular world political power takes the place of God and demands sacrifice, not of the ram but of Isaac. Thus ram and vulture, the brute unconscious forces of the world, triumph over humanity and its faith in covenants or social contracts, even in the land of Abraham. Man becomes only a statistic, the protagonist of a Pieta without salvation; denied the heroism of a Prometheus, he dies for the sake of old values and covenants, which themselves had already been sacrificed to the cause of political and militarysurvival.

This is the historical and moral drama which Kadishman presents in compressed, iconic and monumental clarity Like the sculpture of the later Lipchitz, these works are baroque in their exploration of intangible absolutes and their flirtation with melodrama But Kadishman is saved from excess by the very resistance of his chosen medium, which is not modelled clay or plaster but welded steel; and he also transcends the Judaic tradition which inspired him For a betrayed and dying Isaac, or a once nomadic shepherd struck down on his own Promised Land, is none other than Everyman; trapped in a morally ambiguous world beneath mute and ever more distant heavens.

What kind of art is this which subordinates all its mastery of style and aesthetics to the moral dimensions of human society which reminds us of lost values and broken covenants, and which is more tragic than celebratory or even redemptive? it is an admonitory art, addressing itself to issues that are too important to be left in the hands of generals, bankers and politicians, but that few artists have the will or vision to confront. lt is an art that reaches past the completed edifice of modernism to David, Goya, Delacroix and Courbet and to their common dedication to the values of responsible freedom; to modernity itself But this admonitory art is a new kind of modernity which encompasses the old modernism and is more about a present, and a possible future, than it is about the past.