‘Draw Me a Sheep’ by Sara Breitberg-Semel

Something predictable has happened to painting. During the last fifteen years it has been regarded as the unnecessary, heavy-handed, impure art form-the flesh that covers the skeleton. The interest lay in the skeleton, not in the flesh.

Something predictable has happened to painting. During the last fifteen years it has been regarded as the unnecessary, heavy-handed, impure art form-the flesh that covers the skeleton. The interest lay in the skeleton, not in the flesh.

It was Conceptual Art that left painting out, its motto being `art as idea’, denoting on the one hand rejection of manual work, and on the other focusing on presentation of an idea through necessary, barely sufficient, i.e., minimal, means. Drawing, which was a popular medium during the Conceptual Art period, was presented as a direct and minimal technique for the concretization of an idea. Art products were described in an apologetic tone as documenting an idea whose physical existence was merely temporary (the `Running Fence’ drawings of Christo, Kadishman’s painted tree prints, and photographs of earth works). In that atmosphere, painting was rejected as a medium in which the quality of an artwork is determined by the actual execution rather than by the idea behind it. Colour was rejected as an unnecessary ornamentation which overshadowed the idea, as opposed to the black-and-white drawing which illuminated thought. The works of art characteristic of the period whose end-or at least the end of its militant phase-we are witnessing, were temporary projects, performances, black-and-white drawings, meager painting, conceptual minimal sculpture, video art, etc.

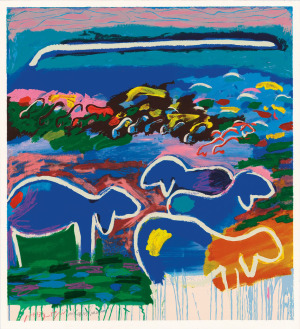

Fifteen lean years have generated thirst. And today, he who is thirsty seeks  the source of water.This is the predictable development which has taken place in painting. The younger generation, which was brought up on Conceptual Art, and which until recently has not been aware of its predecessors, is today discovering painting in an almost passionate manner. An abundance of paint, in contrast with black-and-white, much expression, as opposed to the conceptual idea, much romanticism, as opposed to conceptual rationalism. In historical terms, we are concerned with a thesis and an anti-thesis, and not yet, in my estimation, with the phase of synthesis. `What are the expectations from the new painting? What is its main concern? Certainly not the painterly quality in its conventional sense, if only because we are dealing with a generation which was not educated in the culture of painting and which is unfamiliar with its subtleties. This generation lacks the tools to produce a lassically constructed and refined painting, and to a great extent it also lacks the patience to do so. The painting of the younger generation is close in spirit to the American Action Painting. It is a kind of demonstration of life and emotion, and a substantial part of its strength emanates from its rejection of the Conceptual past.

the source of water.This is the predictable development which has taken place in painting. The younger generation, which was brought up on Conceptual Art, and which until recently has not been aware of its predecessors, is today discovering painting in an almost passionate manner. An abundance of paint, in contrast with black-and-white, much expression, as opposed to the conceptual idea, much romanticism, as opposed to conceptual rationalism. In historical terms, we are concerned with a thesis and an anti-thesis, and not yet, in my estimation, with the phase of synthesis. `What are the expectations from the new painting? What is its main concern? Certainly not the painterly quality in its conventional sense, if only because we are dealing with a generation which was not educated in the culture of painting and which is unfamiliar with its subtleties. This generation lacks the tools to produce a lassically constructed and refined painting, and to a great extent it also lacks the patience to do so. The painting of the younger generation is close in spirit to the American Action Painting. It is a kind of demonstration of life and emotion, and a substantial part of its strength emanates from its rejection of the Conceptual past.

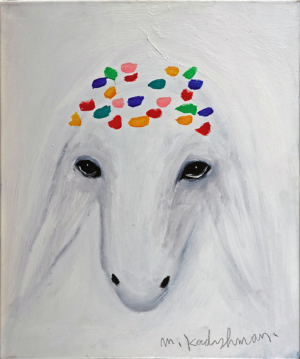

Its aesthetic concepts, still not consolidated, include such words as freshness, vivacity, vigour, dynamics, personality. And here Kadishman enters the scene. Menashe Kadishman, an artist in his prime, a reputed sculptor of the St. Martin’s School in the sixties and an artist of interesting projects in the seventies, took up painting two years ago. A special case. Question; Kadishman, why did you suddenly start painting? Answer; It all began with prints. After the Biennale, I made many prints from the photographs I had of the flock of sheep I exhibited there and of the tree sculpture series. I would go to the printers choose a colour, and paint. I loved the preoccupation with paint. Later, I got the idea of continuing and extending the possibilities of colours. I asked the printer to print the photographed sheep on linen sheets which I brought from home, instead of on paper, and I would paint patches of colour on the backs of the printed sheep, as I had done at the Biennale. These were my first paintings. But my preoccupation with colour goes still further back in many works. Even at the Biennale, where I exhibited the flock of sheep, I painted their backs blue.

Kadishman describes the sequence of events as they occurred. We, on our part, can list additional precedents which support this relatively long-standing affinity between Kadishman and paint: his painted metal sculptures of the sixties

Kadishman describes the sequence of events as they occurred. We, on our part, can list additional precedents which support this relatively long-standing affinity between Kadishman and paint: his painted metal sculptures of the sixties

(`Suspense’ of 1965, a yellow sculpture in the sculpture garden of the Israel Museum in Jerusalem; ‘In Suspense’ of l96o, a blue sculpture in the Tel Aviv Museum); the yellow metal forest, first exhibited in Montevideo, Uruguay; the telephone-book pages done in the seventies, with which from the dullest of books he created fascinating colour pages. The yellow-painted tree in the Valley of the Cross, and the pink- and blue-painted trees in Tel Hai are additional precedents. In other words, his inclination for paint had existed before, as had his involvement in the world art scene (the shift from sculpture to projects in the seventies) and as had his attraction to nature. But above all, there has always been an individual approach to art, emphasizing the joy of creating, the sense of fun, the relating to ordinary and basic things around us, and the fascinating originality in the shaping of images and forms. He has the ability to produce original forms from next to nothing.

Not favouring any particular material, as is common among sculptors, he is able to perceive everything as material for art, not defining but rather blurring the technical boundaries: painting-sculpture-projects-objects and all

their possible combinations. Everything can come into account. Today it’s glass, tomorrow a page of a telephone book, and the day after the painting itself becomes material, a sheep, a tree, nature.

His touching of nature is cautious, harmless. He is not the `rapist’ artist. He is the kind of artist who conquers nature seductively in order to increase charm and beauty. Reflecting on his overall involvement in nature-the painted sheep and

trees, the metal forest within the real forest-one pictures him as the ‘makeup artist’ of nature who underlines beauty, but, whose contribution is removable.

As is his approach to material and the shaping of forms, so is his approach to the creation of images: very direct and simple. So simple that no artist will be able to touch his imagery. Variations by others on a theme of Kadishman’s are not

possible. There will be no others painting pages of a telephone book nor others colouring trees, neither will there be another `laundry’ forest hung at the Israel Museum.

The common denominator of Kadishman’s diverse images is his ability to recall childhood and its mode of thinking. It is important to distinguish between that art which imitates childish techniques with which we are closely familiar, and

between Kadishman’s art which seems not to have lost the child’s vision and manner of thinking. Kadishman’s entire creativity within its various periods, its various forms, has always included the realms of childhood. Through this ability of

his, one can acquire a second taste of those things which had once impressed us (the `laundry’ forest, metal suspended in the air), of the things dreamed of then (`Draw me a sheep’, begged the little prince); even of the painterly solutions of

childhood (the erasing of names in a telephone book with coloured pencils, the tree negatives which resemble children’s paper cutouts, the technique in painting of filling space with patches of colour). His fondness of `kitsch’ as well is

explained when seen against this background of what is called `the taste of childhood’, like the pasting of flowers on a painting.

Joining the new tidal wave of painting, he does so only with his unorthodox approach to the painterly professional tradition and its values. He differs from the others in his existential stand and hence in his stand as a painter. His aesthetic

and stylistic conception of painting leans on the long tradition of the colour-patch abstract with which he is well familiar, but the manner of execution is vivacious, liberated, and innocent, like that ofa loud inscription on a street wall.

`Draw me a sheep`, begged the little prince, and Kadishman does. Many sheep, giant portraits of sheep. Kadishman’s sheep is free of any artistic, religious, or national associations. It is not a homage to Rauschenberg’s goat, nor is it a model

of the homeland landscape as in Danziger’s interpretation, although it may evoke the sense of man’s relation to the land. In the language of imagery, Kadishman`s sheep is merely a `timid sheep’ which he perceived as worthy of a magnified

portrait. A small subject, a giant portrayal. In an era of sophistication, he has sought to paint the possibility of contact with ordinary and real things.